Intelligence and the Future of Work

Intelligence isn't uniquely human, it's any system processing information purposefully. From flint axes to AI, tools have extended our capabilities. Today's challenge: integrating AI into services effectively, redefining roles around human skills like empathy and judgement.

What Is Intelligence?

When most people hear the word intelligence, they think of human abilities: solving complex problems, reasoning abstractly, creating art, planning for the future, or debating philosophy. Intelligence is often framed as something uniquely human, a trait that sets us apart from all other living beings. This anthropocentric definition emphasises learning, problem-solving, logical reasoning, decision-making, and foresight. But such a view may be too narrow.

A broader definition is possible: intelligence is the ability to comprehend and purposefully react to information, usually sensory data from the environment. This reframing opens the door to recognising intelligence not as a uniquely human possession, but as a property that exists in many forms across biology and even within artificial systems.

Intelligence as an Adaptive Tool

Seen through the lens of evolution, intelligence is not a luxury trait, but an adaptive tool. Life is defined by its ability to process information and respond in ways that support survival and reproduction. From this perspective, intelligence is not limited to conscious thought or symbolic reasoning. It is any system's capacity to process environmental input and act in ways that increase its chances of persisting.

Human intelligence represents one particularly advanced branch of this evolutionary tree, but not the only one. Consciousness allows for self-awareness, reflection, and deliberate planning. These qualities amplify our ability to use information, going beyond simple stimulus-response patterns into realms of creativity, empathy, and abstract reasoning. Yet many intelligent behaviours in humans occur unconsciously. Consider reflexes, intuitive decisions, or learned habits. They are purposeful reactions to information, but not always filtered through awareness.

Intelligence in Tools and Systems

When we apply the broad definition (the ability to comprehend and purposefully react to information), intelligence need not be biological. Machines already display elements of this. A thermostat comprehends temperature and reacts by turning heating on or off. Artificial intelligence systems take in vast amounts of data, detect patterns, and generate actions, from recommending a product to optimising supply chains.

The key difference is not whether these are examples of intelligence, but whether they embody human-like intelligence. Machines do not yet possess consciousness or general adaptability. However, within their designed domains, they meet the criteria of processing information and reacting purposefully.

Reframed in this way, intelligence is a spectrum, not a fixed category. It is not something that either exists or does not, but something that emerges in varying degrees and forms wherever information is processed in meaningful ways.

From Flint Axes to Artificial Intelligence

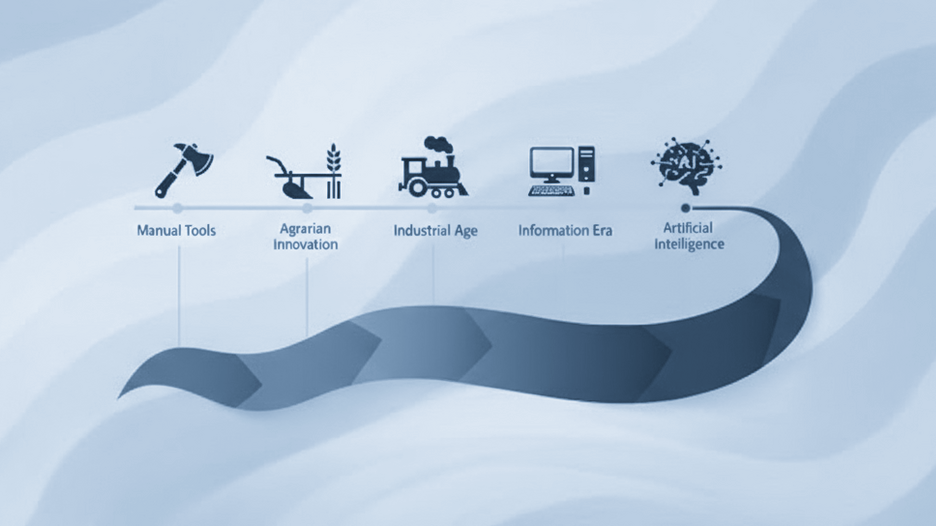

If intelligence is the ability to comprehend and purposefully react to information, then human progress can be told as the story of how we have extended and amplified our intelligence through tools.

The first chipped flint axes were a breakthrough in cognitive projection: early humans observed the hardness of stone, imagined a cutting edge, and shaped it accordingly. This was not just survival but foresight.

The wheel and the plough translated raw human and animal energy into productive force. Societies that adopted these tools transformed landscapes, cultivated surpluses, and built settlements. Intelligence was no longer just in the mind; it was embedded in the artefacts of daily life.

The Industrial Revolution magnified this trend. Steam engines, textile mills, and mechanised production embodied centuries of accumulated know-how. Each machine was a crystallisation of problem-solving. Here, intelligence began to operate at scale, enabling entire nations to reimagine work, trade, and social organisation.

The dawn of computing marked another leap. Where the flint axe extended human strength, and the steam engine multiplied human effort, the computer extended human cognition. Information itself became the raw material of work, and society's most valuable tools were no longer physical objects but abstract processes: algorithms, codes, and programs.

Now, with artificial intelligence, we are at a new inflection point. For the first time, we are creating tools that do not just extend our intelligence but display a version of intelligence in their own right. AI systems learn patterns, adapt to feedback, and make decisions that affect billions of lives. They do not think like us, nor are they conscious, but they fulfil the broader definition of intelligence: they comprehend information and act purposefully.

Intelligence and the Modern Workforce

At each stage in history, societies and organisations that embraced these tools gained competitive advantage. The mechanised factory outproduced the artisan. The computerised office eclipsed the paper ledger. Today, businesses face a similar turning point with artificial intelligence.

The question for organisations is not whether AI is intelligent, but how to integrate it effectively into their operations. The challenge lies in understanding which aspects of work benefit from augmentation and which require distinctly human capabilities.

The Service Economy in Transition

Service industries, which now dominate developed economies, face particular opportunities and challenges. Unlike manufacturing, where automation primarily replaced physical labour, AI in services affects cognitive work directly.

Consider the evolution already underway:

Customer service has seen the introduction of chatbots and virtual assistants that handle routine enquiries, freeing human agents to address complex, emotionally nuanced situations. The pattern is not wholesale replacement but a division of labour between artificial and human intelligence.

Financial services now use AI for fraud detection, risk assessment, and algorithmic trading. Yet relationship management, strategic advisory, and ethical judgement remain firmly in human hands. The most successful firms blend machine precision with human wisdom.

Healthcare is witnessing AI-assisted diagnostics, with systems detecting patterns in medical imaging that human eyes might miss. However, the consultation, the bedside manner, the weighing of quality of life considerations, these remain irreducibly human contributions.

Legal services have adopted AI for document review and legal research, tasks that once consumed junior lawyers' time. This has not eliminated legal roles but shifted them towards interpretation, strategy, and client counsel.

Education is exploring personalised learning platforms that adapt to individual student needs, driving agency. Yet the role of teachers as mentors, motivators, and role models remains central. Technology augments; it does not replace the relational core of teaching.

Redefining Roles, Not Eliminating Them

The pattern across service industries suggests not elimination but evolution. Roles are being redefined around what humans do distinctively well: exercising judgement in ambiguous situations, building trust, navigating ethical complexity, and bringing creativity to open-ended problems.

This shift requires organisations to rethink workforce development. The question is no longer simply 'what skills does this role require?' but 'how does this role combine human and machine intelligence effectively?'

Several principles are emerging:

Complementarity matters more than competition. The most productive arrangements pair AI's pattern recognition and processing speed with human contextual understanding and ethical reasoning.

Emotional intelligence gains value. As routine cognitive tasks become automated, skills like empathy, persuasion, and relationship-building become differentiators. Service industries, in particular, will prize workers who excel at the human dimensions of work.

Adaptability becomes essential. Workers will increasingly need to learn new tools, interpret AI outputs critically, and adjust as systems evolve. The ability to work alongside intelligent systems, understanding their capabilities and limitations, will be as fundamental as computer literacy became in previous decades.

Judgement under uncertainty remains human. AI excels with patterns in historical data but struggles with unprecedented situations, ethical dilemmas, and decisions requiring cultural sensitivity. These remain domains where human intelligence is indispensable.

The Strategic Imperative

For business leaders, the arrival of artificial intelligence presents both opportunity and obligation. The opportunity lies in productivity gains, improved decision-making, and the ability to serve customers at scale with unprecedented personalisation.

The obligation is to manage this transition thoughtfully. History shows that technological shifts reshape work in ways both intended and unforeseen. The plough brought agriculture, but also new forms of social organisation. The steam engine brought prosperity, but also disruption and inequality. Computers brought connectivity, but also new vulnerabilities.

Organisations that navigate this transition successfully will likely be those that:

Invest in reskilling and upskilling their workforce, preparing employees to work effectively alongside AI systems rather than viewing them as threatened by those systems.

Redesign workflows around human-machine collaboration, thoughtfully allocating tasks according to comparative advantage rather than simply automating existing processes.

Maintain focus on distinctly human value, particularly in service industries where trust, empathy, and ethical judgement drive customer relationships and brand reputation.

Address workforce concerns transparently, acknowledging both the opportunities and challenges that AI presents while building cultures of continuous learning.

Where This Takes Us

Looking ahead, intelligence may become increasingly distributed across biological and artificial systems. Human cognition will coexist with machine learning, creating hybrid systems where decisions are shared between people and algorithms. Work will shift once more, not away from intelligence, but into new forms of collaboration with it.

If we define intelligence broadly (as the ability to comprehend and purposefully react to information), then the trajectory points to an expanding web of intelligence across human and artificial domains. The task for organisations is not to defend the uniqueness of human intelligence, but to ensure that the tools we create amplify our collective capabilities.

The flint axe cut wood and bone. The plough tilled the soil. The engine harnessed steam. The computer mastered symbols. Artificial intelligence is now learning to navigate the open-ended patterns of the world itself. Where this takes organisations and their workforces will depend less on whether machines are truly intelligent, and more on whether business leaders are wise enough to integrate their intelligence well.

The opportunity is substantial. The organisations that thrive will be those that view AI not as a replacement for human workers, but as a powerful complement to human capability, one that allows people to focus on the work that requires our distinctly human forms of intelligence: creativity, empathy, ethical reasoning, and judgement under uncertainty.

Next

Over the history of mankind, the main drivers of workforce productivity, and therefore of an increase in a society's standard of living, are man's adoption of tools and of the availability of capital investment to procure better tooling.

Received corporate wisdom over the last several decades has to been to drive for efficiency. But true gains come from productivity.