The Paradox of Tolerance

When tolerance is extended to intolerant behaviours, it can erode the very freedoms it aims to protect. To prevent this, organisations must set clear boundaries, promote respectful dialogue, and ensure inclusion is principled, not passive.

Inclusivity and tolerance are widely regarded as pillars of modern organisational culture. They underpin diversity initiatives, foster psychological safety, and enable open dialogue. Yet, as philosopher Karl Popper warned in his seminal 1945 work The Open Society and Its Enemies, tolerance has a paradox: if extended without limits - even to intolerant ideologies - it risks enabling forces that ultimately dismantle the very freedoms it seeks to protect. This article explores how that paradox manifests in the workplace, where well-intentioned inclusivity can inadvertently create environments vulnerable to manipulation, dominance, and division.

The piece begins by contextualising Popper’s paradox within organisational life, highlighting howpluralistic cultures - when not actively managed - can be exploited by individuals or groups who suppress dissent, monopolise psychological safety, or resist accountability. It examines how silence, ambiguity, and fear of confrontation can allow intolerance to flourish, eroding trust and engagement across teams.

Drawing on workplace psychology and leadership practice, the article explores how tolerance can be mismanaged in organisational settings. It highlights how concepts like psychological safety can be misused, how power dynamics can distort team interactions, and how vague or overly broad policies can fail to prevent harmful behaviour. These patterns show how passive tolerance - tolerance without boundaries or accountability - can lead to cultural drift, disengagement, and a breakdown of trust.

The article also provides practical guidance for individuals, offering strategies to recognise and respond to intolerance with ethical courage and empathy. It emphasises the importance of principled tolerance - one that is active, resilient, and capable of drawing boundaries without compromising openness.

For leaders, the article outlines imperatives for building trust and engagement in the face of this paradox. It advocates for clarity, consistency, and transparency, alongside systems that support pluralism and accountability. Leaders are encouraged to foster inclusive dialogue, defend democratic norms within their organisations, and ensure that tolerance does not become a shield for harmful behaviours.

Ultimately, the article calls for a thoughtful balance: a workplace culture that embraces diversity of thought and identity, while refusing to tolerate actions or ideologies that seek to undermine that diversity. It positions tolerance not as a passive virtue, but as a dynamic practice - one that requires vigilance, courage, and leadership.

Understanding the Paradox

The philosophical roots of the paradox

Karl Popper framed the “paradox of tolerance” simply: a society or system that tolerates intolerance without limit ultimately destroys the conditions that make tolerance possible.

In the workplace, this offers a practical warning for leaders: when the expectation of shared involvement and mutual respect lacks structure, it can be exploited. If organisations fail to set clear boundaries around acceptable behaviour, the openness intended to foster collaboration and trust can be misused by those who seek to dominate, silence, or exclude others.

In such cases, the idea of everyone having a voice becomes a shield for intolerance, not because the principle is flawed, but because it lacks the clarity and safeguards needed to prevent misuse. The solution isn’t less openness or participation, it’s more intentional engagement, guided by clear norms, accountability, and a shared understanding of what tolerance truly requires.

Two clarifications that are helpful in organisations:

- Tolerance ≠ agreement: It’s the discipline of allowing disagreement without allowing harm.

- Inclusion ≠ unfiltered permissiveness: It’s the commitment to fair voice, safety and dignity - paired with boundaries that protect those commitments.

How it manifests in society - and in organisations

We recognise the paradox outside work in public discourse turning brittle, where “free speech” is invoked to justify harassment, or where “safety” is used to shut down dissent. Inside organisations, the same pattern shows up more quietly:

- Language capture: Terms like “unsafe”, “allyship”, or “fairness” are used to deflect feedback rather than enable it.

- Norm drift: Meetings become performative; a few voices set the tone while others self‑censor.

- Policy gaps: Values are inspirational but operational guardrails are missing, so decisions feel arbitrary or political.

When tolerance backfires at work

- The “mission defender”

A passionate senior engineer positions themselves as guardian of the product’s “true vision.” They publicly challenge peers as “not customer‑centric,” escalating tone when disputed. Managers, keen to “respect strong opinions,” avoid intervening. Over time, team members route around the engineer; retrospective meetings become muted; exit interviews cite “brilliance bias” and “no room to contribute.” Tolerance of one person’s intensity crowds out collective problem‑solving. - The “safety shield”

In a transformation programme, a manager resists data transparency, saying “sharing this will make my team feel unsafe.” The language of psychological safety is used to block scrutiny of missed commitments. Without a principled boundary - “safety supports learning; it never prevents accountability” - the programme slips and trust erodes. - The “values veto”

A cross‑functional forum is created for robust debate. A small group repeatedly labels alternative views as “anti‑values.” Colleagues stop offering counter‑proposals. Leaders, worried about reputational noise, cancel the forum. The result: decisions move offline, influence concentrates, inclusivity narrows.

Working truth: When shared involvement lacks boundaries, it becomes a tool for the loudest or most dominant. When guided by clear expectations, it becomes a platform for broader contribution.

When Tolerance Is Misused: How Workplace Culture Can Enable Intolerance

Tolerance needs boundaries to be effective

In the modern workplace, tolerance is often seen as a virtue - an essential ingredient for collaboration, diversity, and psychological safety. Organisations strive to create environments where people feel free to express themselves, challenge ideas, and bring their full selves to work.

But tolerance, when left unchecked or poorly defined, can be misused. It can become a shield for behaviours that silence others, derail progress, or erode trust. This isn’t a failure of tolerance itself, it’s a failure to manage it well.

When tolerance becomes passive - when it avoids confrontation or accountability - it creates space for dominance and manipulation. People may exploit the culture of openness to push harmful ideas, shut down dissent, or avoid responsibility. Over time, this erodes the very values that tolerance is meant to protect.

To prevent this, organisations must:

- Define what tolerance is and isn’t: Tolerance means respecting different views, not accepting behaviour that undermines others.

- Set clear expectations: Everyone should know what respectful challenge looks like, and what crosses the line.

- Hold people accountable: Tolerance must be mutual. It cannot protect one person’s freedom at the expense of another’s dignity.

Tolerance should empower people to speak up, challenge ideas, and learn from each other. But it must also come with boundaries, so that it doesn’t become a tool for exclusion or control.

In a healthy workplace, tolerance is active, principled, and shared. It’s not about avoiding conflict, it’s about handling it well.

The misuse of psychological safety

Psychological safety, a term popularised by Harvard professor Amy Edmondson, refers to a climate in which individuals feel safe to take interpersonal risks - such as speaking up, admitting mistakes, or challenging the status quo. It’s a powerful enabler of learning and innovation. But when misunderstood, psychological safety can be weaponised.

Consider the following scenarios:

- A team member consistently shuts down others’ ideas, claiming they feel “unsafe” when challenged.

- A leader avoids giving constructive feedback for fear of being perceived as intolerant or insensitive.

- A vocal minority dominates discussions, while others withdraw to avoid conflict.

In each case, the language of safety is used to suppress dissent, not to foster dialogue. The result is a culture where intolerance masquerades as vulnerability, and where genuine diversity of thought is stifled.

The tipping point: when silence enables dominance

Tolerant cultures often emphasise listening, empathy, and non-judgment. These are essential traits - but they can also lead to avoidance of difficult conversations. When intolerance arises - whether in the form of discriminatory remarks, exclusionary behaviour, or ideological rigidity - teams may hesitate to respond. The fear of being labelled as confrontational or “intolerant of difference” can lead to silence.

This silence is not neutral. It creates a vacuum that intolerant voices can fill. Over time, these voices may begin to shape team norms, influence decision-making, and marginalise others.

The paradox unfolds: tolerance of intolerance erodes tolerance itself.

The role of organisational systems

Organisations often rely on policies, training, and values statements to support a culture of shared involvement. But these systems can be inadequate or misaligned:

- Policies may be too vague, failing to define what constitutes intolerant behaviour.

- Training may raise awareness, but not equip employees to act when intolerance occurs.

- Values may be aspirational, but not embedded in performance management, leadership development, or conflict resolution.

Without clear boundaries and accountability mechanisms, cultures built on openness and participation become vulnerable. The paradox of tolerance thrives in ambiguity.

The influence of power dynamics

Intolerance in the workplace is rarely overt. It often hides behind power dynamics - who gets to speak, who is listened to, who wins the prize, who is promoted, and who is protected. Reference Rituals and Routines in Understanding and Changing Corporate Culture. When individuals or groups use their influence to silence others, reward favourites, resist feedback, or enforce ideological conformity, they exploit the tolerance of the system.

Leaders play a critical role here. Their silence, indecision, or inconsistency can signal tacit approval. Conversely, their clarity, courage, and fairness can restore balance.

Cultural drift and the erosion of trust

Over time, unchecked intolerance leads to cultural drift. Teams become fragmented. Trust erodes. Engagement declines. Employees begin to self-censor, disengage, or leave. The organisation may still claim to be pluralistic, but the lived experience tells a different story.

This drift is often invisible until it becomes a crisis - an HR investigation, a public scandal, or a wave of resignations. By then, the cost of inaction is high.

Tolerance is not passive

Tolerance in the workplace isn’t just about being open, it’s about being intentional. It’s not a passive state of letting things slide; it’s an active practice that requires vigilance, courage, and clarity.

To be effective, tolerance must be principled, not permissive. It should support respectful disagreement, not protect harmful behaviour. Psychological safety must be shared, not monopolised. And silence must never be mistaken for respect.

True tolerance means creating space for difference, while standing firm against behaviours that undermine trust, dignity, or fairness.

Individual Responses to Perceived Intolerance

Leaders should equip employees to recognise intolerance early, respond proportionately, and model principled civility - without burning social capital or personal wellbeing.

Recognise the pattern - fast, fairly, and factually

Use the SBI+H model (Situation:Behaviour:Impact + Hypothesis).

SBI+H is a framework for giving constructive feedback by first describing the Situation (when and where), then the observable Behaviour (what happened factually), followed by the Impact (the effect on you and others), and finally adding a Hypothesis to explore the person's intent or offer a suggestion for the future.

The Hypothesis step is crucial for turning feedback into a collaborative learning opportunity, moving beyond simply stating a problem to understanding the underlying reasons and finding solutions together.

- Situation: “In yesterday’s stand‑up…”

- Behaviour: “…two ideas were labelled ‘unsafe’ without specifics.”

- Impact: “…the group stopped contributing; we lost two viable options.”

- Hypothesis (tentative): “…I wonder if ‘unsafe’ is being used as a veto rather than a prompt for clarity.”

If you can’t describe it behaviourally, you’re not ready to challenge it. If you can, you can.

Red flags that signal the paradox at play:

- Vague claims (“unsafe”, “offensive”, “anti‑values”) without examples.

- People pre‑emptively apologising for speaking.

- Debates ending with labels, not reasons.

Build personal resilience and ethical courage

Each of us can have a simple pair of anchors to carry into any room:

- Your standard: “Dignity, evidence, and effort.” If any of these are compromised, that’s your cue to speak.

- Your boundary: “I’m very open to disagreement. I’m not open to dismissal without reasons or respect.”

Three practices that will help you stay in control:

- Pre‑commit: Before difficult forums, write the one point you must make. It halves the chance you’ll self‑censor.

- Micro‑recovery: Box‑breathing (4–4–6–2) between agenda items will keep you calme and reduce reactive language. The 4-4-6-2 breathing technique is a simple, deep-breathing exercise that involves inhaling for 4 seconds, holding your breath for 4 seconds, exhaling slowly for 6 seconds, and then pausing for 2 seconds. This method helps to activate the body's relaxation response, which slows your heart rate and calms your mind, providing a powerful tool for reducing stress and anxiety.

- Ally‑pairing: Agree with a colleague to backstop each other with conversational links and clarifying questions.

Navigate difficult conversations with empathy and clarity

Use ACE: Acknowledge – Clarify – Establish.

- Acknowledge (their concern): “You’re flagging safety - that matters.”

- Clarify (ask for reasons/evidence): “Which part specifically creates risk? For whom, and how would we know?”

- Establish (a fair rule): “Let’s continue if we can ground these claims in evidenced examples. Otherwise, we’ll park it and return with data.”

Alternative quick frameworks:

- CARE (Curiosity, Accountability, Respect, Evidence) for feedback.

- RISK (Reason, Impact, Specifics, Keep‑doing/Change) for escalations.

- Two‑turn rule in meetings: no one speaks twice until everyone who wants to has spoken once.

When to escalate:

- Repeated pattern of responses after feedback has been given.

- Power asymmetry makes direct challenge unsafe.

- Behaviours breach policy (discrimination, harassment, retaliation).

Escalate with SBI+H notes and a neutral ask: “Would it be OK if we brought an independent facilitator to our next session?”

Leadership Imperatives

Tolerance in the workplace isn’t just a cultural preference, it’s a strategic governance decision. As a leader, your role is to set clear boundaries, enforce them consistently, and build trust through transparency.

Draw boundaries without undermining trust

To foster a culture of principled tolerance, organisations must balance autonomy with structure. One effective approach is Freedom within a Framework, a leadership model that empowers teams to make decisions while operating within clearly defined guardrails and shared values. It’s about devolving decision rights to where they’re most effective, while ensuring those decisions align with the organisation’s purpose and standards.

This approach works when leaders:

- Clarify what’s non-negotiable - such as dignity, evidence-based decision-making, and fair process.

- Allow wide latitude - for style, challenge, and dissent, as long as it’s constructive.

- Make expectations explicit - for example: “You’re free to speak up, and are accountable for how you do it.”

Tolerance, when governed well, creates space for difference without compromising cohesion. It’s not about avoiding conflict, it’s about managing it with integrity.

This model works best when everyone understands what’s non-negotiable and where there’s room for flexibility.

Bright Lines: what’s non-negotiable

These are the behaviours that protect dignity, fairness, and trust. They apply to everyone, regardless of role or seniority.

- Respect the Person: Critique ideas or roles - not identities. No sarcasm, personal attacks, or comments based on race, gender, or background.

- Back It Up: If you’re raising a concern that stops progress, bring examples or data - not just opinions.

- Follow the Process: Disagreements should be handled in the room first. If needed, escalate through a clear, fair path.

Wide Latitude: what’s open to interpretation

These are areas where people can express themselves, challenge norms, and bring creativity, without fear of being shut down.

- Different communication styles

- High levels of challenge or debate

- Unconventional ideas

- Constructive dissent.

Make it clear: “Psychological safety means you can speak up and be accountable for how you do it.”

This approach helps teams stay aligned without becoming rigid. It encourages innovation and debate, while protecting the culture from behaviours that erode trust. Leaders should reinforce these boundaries regularly, not just in policy, but in how they respond, coach, and model behaviour.

Trust comes from clarity and consistency

Trust isn’t built by accident, it’s the result of leaders being clear in what they decide, and consistent in how they follow through. Here’s how to make that real:

Make Decisions Transparent

- Use Decision Logs: Share key decisions, the reasons behind them, and what alternatives were considered. This builds understanding and reduces second-guessing.

- Lead with Principles: Define 5 to 7 guiding principles for decisions, especially around strategy and people. Refer to them in communications:

“We chose X because it aligned with Principles 2 and 4.”

Act When Boundaries Are Crossed

- Respond Clearly: If someone crosses a line, explain what happened and why it matters. Keep it calm and direct... no drama, no silence.

- Avoid Mixed Signals: Ignoring bad behaviour looks like approval. Overreacting looks political. Aim for fair, visible consequences.

Use Language That Reinforces Culture

Leader phrases that help set the tone:

- “I welcome challenge; I won’t accept contempt.”

- “Strong views, strongly examined.”

- “We protect people; we interrogate ideas.”

These habits don’t just build trust, they protect it.

Create Systems That Support Tolerance and Accountability

Tolerance in the workplace must be more than a cultural aspiration, it needs to be operationalised. That means building systems that protect pluralism while preventing the misuse of openness. When organisations fail to do this, they risk allowing intolerant behaviours to flourish under the guise of inclusivity.

Start by moving from slogans to mechanisms. Pilot small changes before scaling. Make tolerance visible in how decisions are made, how feedback is given, and how dissent is handled.

Design for principled pluralism

Pluralism isn’t just about diversity, it’s about ensuring that multiple viewpoints can coexist without being dominated or silenced.

- Mixed-tenure panels for hiring and promotion: Blend experience levels and backgrounds to reduce bias and avoid echo chambers.

- Deliberate minority reporting: Actively capture dissenting views in major decisions. This prevents efficient groupthink and ensures that tolerance doesn’t mean ignoring uncomfortable truths.

- Rotate meeting roles: Give different people the chance to lead, challenge, and summarise. It distributes influence and prevents dominance.

These systems ensure that tolerance is structured, not passive, that it includes difference without enabling intolerance.

Make accountability a tool for learning, not control

Tolerance doesn’t mean avoiding feedback - it means giving it fairly and constructively.

- Use SBI + Remedy: Describe the Situation, Behaviour, and Impact, then clearly state what needs to change. This keeps feedback grounded and actionable.

- Run learning-oriented reviews: After key projects, reflect on what happened and who was heard. Use “voice maps” to track participation and identify patterns of exclusion or dominance.

These practices help teams challenge each other without crossing into aggression or manipulation.

Protect the right to speak up, without fear

Tolerance fails when people are afraid to challenge intolerance. Build systems that make speaking up safe and meaningful.

- Trusted triage: Have a neutral person or team review concerns before action is taken. This prevents knee-jerk reactions and protects fairness.

- Test anti-retaliation: Randomly ask, “Did anything change for you after you raised a concern?” Use the data to hold the system accountable.

- Quarterly culture pulse: Ask three simple questions: Did you feel respected? Was evidence used? Was effort recognised? Publish the trends and act on them.

These systems don’t just support a respectful and open culture, they protect principled tolerance. They ensure that openness doesn’t become a loophole for harmful behaviour, and that accountability is used to strengthen trust, not suppress it.

Towards a Thoughtful Balance

Reclaiming tolerance as an active, engaged practice

Tolerance is not the absence of judgement; it’s the presence of disciplined judgement about what we will and won’t permit in the pursuit of our goals. It asks us to:

- Welcome difference of thought while protecting dignity of person.

- Encourage risk‑taking while ensuring repair when harm occurs.

- Keep channels open while preventing forum capture by any faction.

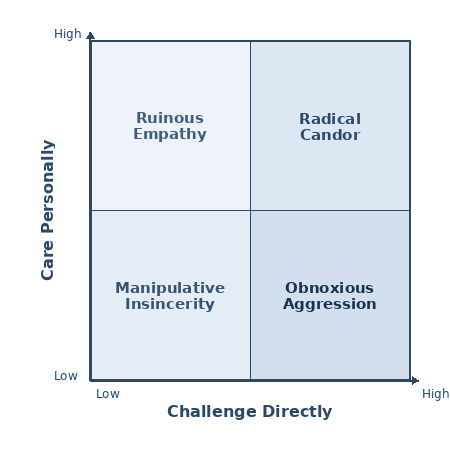

A helpful mental model for teams is the Civility–Candour Grid:

- High Civility + High Candour

→ Radical Candour = Robust Civility (aim here). - High Civility + Low Candour

→ Ruinous Emplathy = Nice but stagnant. - Low Civility + High Candour

→ Obnoxious Agression = Brutal, high churn. - Low Civility + Low Candour

→ Manipulative Insincerity = Apathetic, quiet quitting.

Tools for Leaders: How to Make Dialogue, Feedback, and Culture Work

A. Dialogue frameworks

These are structured ways to make conversations fair, focused, and productive.

1. Runged debate

A method for tackling tough issues without talking past each other:

- Round 1 – Exploration:

Each person explains the other side’s view as accurately as possible.

Why? It forces real listening and reduces misunderstanding. - Round 2 – Evaluation:

Discuss only the strengths and risks of each option.

Why? Keeps the debate constructive instead of personal. - Round 3 – Decision:

Rank the options against agreed principles (e.g., fairness, cost, speed).

How? Use a simple scorecard or sticky notes to vote.

2. Two-column contracts

A shared agreement on expectations:

- Column 1: “What we owe each other” (e.g., honesty, timely updates).

- Column 2: “What happens when we fall short” (repair norms, like apologizing or fixing the issue quickly).

How to implement: Create this together in a team meeting, write it down, and revisit quarterly.

B. Feedback loops

Ways to make feedback a normal, safe part of work.

1. Ritualised feedback

- Spend 10 minutes at the end of key meetings asking:

- What helped people speak up?

- What made it harder?

- Capture answers on a whiteboard or shared doc.

Why? It normalizes reflection and improves meeting quality.

2. Leader listening hours

- Hold open sessions every two weeks with a published theme (e.g., “decision-making transparency”) or no theme, just turn up.

- Share what actions you took based on feedback.

Why? Builds trust and shows feedback leads to change.

3. Signal boosting

- In all-hands meetings or newsletters, highlight examples of constructive dissent (e.g., “Thanks to Alex for challenging our approach on X, it improved the outcome”).

Why? It makes speaking up a visible, rewarded behavior.

C. Cultural audits: a quick check on workplace tolerance

To protect a culture of principled tolerance, organisations need regular, lightweight ways to check whether their environment truly supports openness, fairness, and respectful dissent. A Cultural Audit is a simple, repeatable tool that helps leaders spot early signs of intolerance or exclusion, and act before they escalate.

1. What to measure

Use a short, 10-question survey (Likert scale) to assess:

- Dignity: Are people treated with respect, regardless of role or identity?

- Fairness: Are decisions and opportunities distributed equitably?

- Psychological Safety: Can people speak up and listen without fear?

- Inclusion of Dissent: Are different views welcomed, not sidelined?

- Transparency: Are decisions and processes clear?

- Retaliation Risk: Do people feel safe raising concerns?

These questions help reveal whether tolerance is being upheld, or quietly undermined.

2. Combine data sources

Don’t rely on surveys alone. Add:

- Meeting analytics: Who speaks, for how long, and who gets interrupted?

- Employee relations data: Trends in complaints, conflict, or turnover.

- Exit interviews: What departing employees say about culture and fairness.

Together, these give a fuller picture of how tolerance is lived, not just claimed.

3. Review and act

Quarterly, share a simple update with your teams:

- You said… (Top feedback themes)

- We did… (Actions taken)

- What’s next… (Planned improvements)

This closes the loop and builds credibility. It shows that tolerance isn’t just a value it’s a practice, backed by listening and action.

Cultural audits help organisations stay honest about their culture. They make it easier to spot when tolerance is being exploited or eroded, and to respond before it becomes systemic. When done consistently, they reinforce a workplace where people can speak up, challenge respectfully, and trust that their voice matters.

Final Reflections: Reclaiming Tolerance in the Workplace

In today’s workplace, tolerance is not just a virtue, it’s a strategic necessity. But as we've explored, when tolerance is extended without discernment, it can become a liability. The paradox is clear: if organisations tolerate behaviours that undermine respect, civility, or psychological safety, they risk eroding the very culture they aim to build.

This is especially urgent in a world where polarisation is not episodic, it’s ambient. Organisations now operate in environments shaped by ideological tension, social fragmentation, and digital amplification. In this climate, the companies that endure and thrive will be those that institutionalise principled tolerance, not as a slogan, but as a system of practice.

That means:

- Leaders who draw clear boundaries, not to suppress dissent, but to protect dialogue. They must be willing to say, “This behaviour is not acceptable here,” and follow through with consistency and fairness.

- Teams who treat feedback as a shared responsibility, not a personal attack. Cultures of growth depend on the ability to challenge directly while caring personally, a balance that Radical Candor captures well.

- Systems that set pluralism over performance theatre. Inclusivity must be embedded in hiring, development, governance, and conflict resolution, not just celebrated in town halls or social media posts.

Tolerance, in this context, is not passive acceptance. It is active engagement: the ability to listen deeply, challenge constructively, and stand up for shared values. It is the courage to say “no” to behaviours that harm, even when those behaviours are cloaked in claims of vulnerability or free expression.

As Karl Popper warned, we must claim the right not to tolerate the intolerant. But in doing so, we must also build cultures where difference is welcomed, not weaponised, where disagreement is a source of learning, not division.

The future of tolerance in the workplace depends on our ability to hold this paradox with clarity and care. Not to resolve it, but to navigate it - together, deliberately, and with integrity.