Understanding Knowledge

In a world flooded with data, what does it mean to truly know? This article explores knowledge through six dimensions: from mind and language to technology and ethics, tracing our climb from information to wisdom, and the quiet enlightenment that lies beyond.

What does it mean to know, and what lies beyond? In an age drowning in data, rediscovering the nature of knowledge may be our most urgent task.

From Data to Enlightenment: What Knowledge Is (and Is Not)

The modern world confuses knowing with possessing information. We swim in oceans of data (numbers, recordings, metrics, and machine logs) yet remain unsure whether we know more than our ancestors did.

Data are the raw, unprocessed traces of the world: temperature readings, votes cast, words spoken. Information arises when data are structured, given form and context, a relationship or a meaning. But knowledge goes further. It involves justified understanding: the ability to interpret, connect, and apply information towards insight or action.

To know is to integrate the factual with the meaningful. Knowledge allows a doctor not only to read a patient's chart but to infer a diagnosis; a sailor to read wind and tide; an engineer to predict a bridge's strain before it collapses. It is where comprehension and responsibility meet.

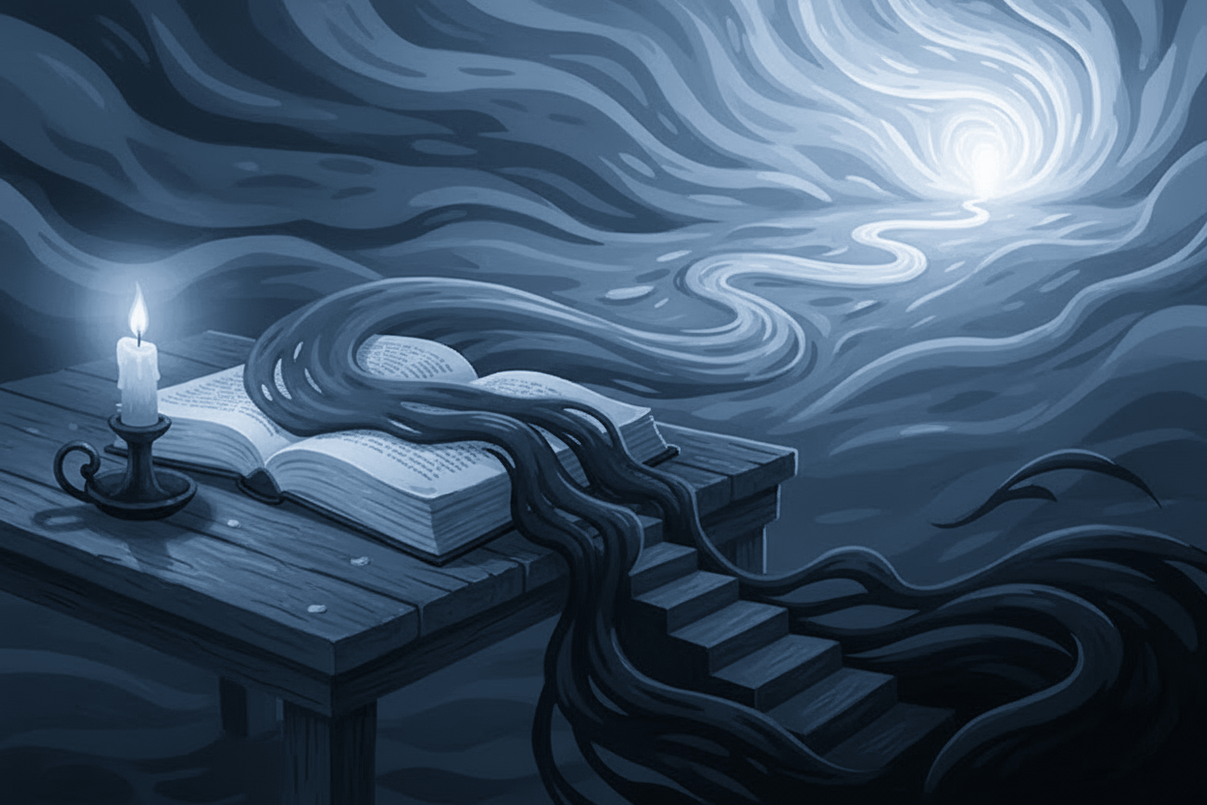

Wisdom, traditionally, is what lies beyond knowledge: the disciplined application of knowledge towards the good. Wisdom asks not what is true, but what ought to be done with what is true. Yet beyond even wisdom, some philosophers gesture towards a still higher stage (call it enlightenment) where knowledge ceases to be possessed and becomes lived: when the distinction between knower and known dissolves. The enlightened do not hold knowledge; they embody it.

In this way, the ladder from data to enlightenment might look like this:

Data → Information → Knowledge → Wisdom → Enlightenment

Each step transforms the previous: from raw measurement, to meaningful pattern, to actionable understanding, to ethical discernment, to a unitive state of awareness. Humanity, at its best, climbs and descends this ladder daily through science, reflection, art, and lived experience.

The Mind at Work: The Cognitive Dimension

Knowledge begins inside the mind, a delicate choreography of perception, memory, and imagination.

When we 'know' something, our brains are not filing away facts like a library clerk; they are sculpting neural pathways, interlinking networks of association. Episodic memory stores experience; semantic memory abstracts principles. Attention filters what's retained, whilst emotion stamps meaning onto the factual.

Crucially, not all knowledge is conscious. The pianist does not 'recall' every motion of the hand; the driver does not compute friction in a curve. These are forms of procedural knowledge: tacit, embodied, resistant to language.

Psychologists and cognitive scientists show that such knowledge is learned by repetition and feedback, not by explanation. It is felt before it is understood. Humanity depends on this quiet substratum: the intuition of a craftsman, the instinct of a nurse, the unspoken rapport between colleagues. The mind, it turns out, knows more than it can say.

Speaking the World: The Linguistic Dimension

To share knowledge, humans invented language, a tool both miraculous and treacherous.

Language encodes experience, but it also shapes it. What can be said tends to become what can be known. The physicist's formula, the poet's metaphor, and the programmer's code are each forms of compression: they make the inexpressible portable.

But every expression distorts as it reveals. Tacit knowledge, for instance (the kind embodied in practice or intuition) resists being written down. It lives in gesture, rhythm, and shared doing. It passes from master to apprentice through observation and imitation, not instruction manuals.

Communities preserve such tacit knowing by embedding it in rituals, habits, and stories. A craft guild, a culinary tradition, a dance form: all are living archives of knowledge that can only be learned by joining the performance. In that sense, language is not only spoken; it is enacted.

Knowing Together: The Social Dimension

Knowledge is never purely private. What we know, we know in communities.

Sociologists call this social epistemology: the study of how knowledge circulates, gains credibility, and becomes institutionalised. A scientific paper, for example, is not knowledge until peers have tested it. A court ruling is not 'known' justice until it is accepted as precedent.

This raises profound questions of trust. Whose knowledge counts? The authority of a medical journal? The testimony of lived experience? In a networked world, where information proliferates faster than verification, society faces an epistemic crisis: a fragmentation of common ground.

Yet cooperation has always been knowledge's great multiplier. The exchange of expertise, mentorship, and debate expands what individuals can know. The social fabric, fragile though it is, remains the medium through which knowledge survives.

Machines of Memory: The Technological Dimension

For millennia, humanity has sought to capture and extend its knowing: first on clay tablets, then paper, and now, vast digital systems.

Information technology represents an evolutionary leap, not in intelligence itself, but in its reach. Databases store; algorithms retrieve; networks connect. Yet machines process information, not understanding. They can mimic knowledge but cannot (so far) mean it.

Still, our tools have become partners in cognition. The historian searches archives that no single scholar could read in a lifetime; the AI model infers patterns invisible to human intuition. We now inhabit a hybrid epistemic landscape where human and machine memory intertwine.

The challenge is curation. Storage has outstripped sense-making. The danger is not forgetting, but drowning: mistaking volume for insight. True knowledge still depends on human discernment: the capacity to filter, interpret, and connect.

Knowing Well: The Ethical and Existential Dimension

Knowledge carries weight. To know something is to stand in relation to it, to bear a kind of responsibility.

Every discovery has ethical consequences: the splitting of the atom, the decoding of genomes, the reach of surveillance. The Enlightenment once promised that knowledge would liberate humanity; it did, but unevenly. In the wrong hands, knowledge can enslave, manipulate, or destroy.

So the question of what we should know becomes as urgent as how much we can know. Some knowledge may be too dangerous, some ignorance too costly. Wisdom, the tempering of knowledge with moral insight, is our only defence.

Yet wisdom is not static either. It grows when knowledge is joined to empathy: when the scientist, the artist, and the citizen each recognise that knowing the world also means caring for it.

The Whole Picture: Towards an Integrated Understanding

Seen together, the six dimensions of knowledge form a living system:

The philosophical dimension defines what knowledge is and how it differs from data or belief.

The cognitive dimension shows how minds form and hold it.

The linguistic dimension explains how we express and transmit it.

The social dimension reveals how we share and validate it collectively.

The technological dimension extends and externalises it.

The ethical dimension directs its purpose and its limits.

Knowledge, then, is not a substance but a relationship: between mind and world, individual and society, meaning and responsibility.

In an era obsessed with artificial intelligence, we would do well to remember that intelligence alone is not wisdom, and that wisdom itself is only a threshold. Beyond it lies enlightenment, a quieter, humbler knowing in which awareness and compassion meet.

Perhaps that is where the next age of knowledge begins: not in the servers of data centres, but in the cultivated minds of those who seek to understand, rather than merely to know.